Some years back, I remember the excitement in the Agile community when the general public started taking us seriously. The common reaction went from “Get away from me, crazy people,” to “That’s interesting; tell me more.” It felt like the car we had been pushing uphill had finally reached the crest.

At the time, it was very exciting. In retrospect, perhaps that was the beginning of our doom: the car passed the crest, picked up speed, and careened out of control. Now the state of the Agile world regularly embarrasses me, and I think I’ve figured out why.

The first chasm

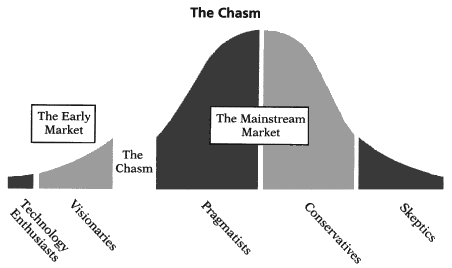

Geoffrey Moore’s seminal book “Crossing the Chasm” is about a gap between a product’s early adopters and the rest of a market. Writing in 1991, he looked at why disruptive technology products fail, and concluded that there was an chasm between the early market for a product and everyone else. Some companies fall in, some cross it to success.

The essence of this is that the early market, who are circa a sixth of the total market, are different. They are comfortable with changing their behavior, and are eager to do it to get a jump on the competition. In contrast, early mainstream purchasers “want evolution, not revolution. They want technology to enhance, not overthrow, the established ways of doing business.” Later mainstream purchasers don’t want to change at all; they do it because they have to. For a physical technology product, that mainly shapes marketing and product accessories like support and documentation. But what does that mean for something as ethereal as a development process or a set of values?

The second chasm

You can’t buy an idea. Instead, people buy things like books, talks, classes, and consulting services. By and large, those buyers don’t measure any actual benefit. When wondering whether they got their money’s worth, they go by feeling and appearance.

For early adopters, that can be enough. As people who seek sincerely and vigorously to solve a problem or gain an advantage, they are strongly motivated to find ideas of true value and to make them work. But for the later adopters, their motivation for change isn’t strong. For many, it’s merely to go along with everybody else, or to appear as if they are.

Because those later adopters are numerically greater, they’ll be the majority of the market. And unlike early adopters, who tend to be relatively self-sufficient, they will consume more services, making them an even bigger influence. They’ll also tend to be the least sophisticated consumers, the least able to tell the difference between the product they want and the product they need.

Putting that together, it suggests that when people want an idea, the most money can be made by selling products that mainly serve to make later adopters look or feel like they’re getting somewhere. Any actual work or discomfort beyond that necessary to improve appearances would be a negative. Bad products and bad ideas could drive out the good ones, resulting in a pure fad. The common perception of the idea would come to be defined by the majority’s behavior and results, burying the original notion.

That’s the second chasm: an idea that provides strong benefits to early adopters gets watered down to near-uselessness by mainstream consumers and too-accommodating vendors.

Agile fell in

From what I can see, the Agile movement has fallen in the second chasm. That doesn’t mean that there aren’t bright spots, or people doing good work. You can, after all, find old hippies (and some new ones) running perfectly fine natural food stores and cafes. But like the endless supply of grubby, weed-smoking panhandlers that clutter San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, I think there is a vast army of supposedly Agile teams and companies that have adopted the look and the lingo while totally missing the point.

Originally, I based this notion on the surprising number of people I talked to who were involved in some sort of Agile adoption that was basically bunk: Iterations that weren’t iterating. Testing that wasn’t testing. Top-down power relationships. Cargo cult Agile. Fixed deadlines and fixed scopes. Teams that aren’t teams. Project managers who pretend to be Scrum Masters. Oceans of Scrumbut.

That could have just been me, of course. But over the past year or so I’ve talked to a number of Agilists that I met in the 2000-2003 timeframe. They have similar concerns. “This isn’t what we meant,” is something I’ve heard a few times, and I feel the same way. Few these days get the incredible improvements we early adopters did. Instead, they get little or no benefit. The activity of the Agile adoption provides a smokescreen, and the expected performance gains become a stick to beat employees with.

Honestly, this breaks my heart. These days, every time an acquaintance starts off saying, “So now we’re ‘doing Agile’ at work…” I cringe. I used to be proud to be associated with the Agile movement. But although I still love many of the people involved, I think what happened is a shame. Looking back, I see things I wish I had done differently, things I intend to do differently next time. Which makes me wonder:

- Have other early Agilists noticed this?

- If you had it to do over again, what would you do differently?

- To what extent do you think the problem is solvable?

I’d love to hear what other people think, be that via email or on Twitter.

*Originally published on Agile Focus.