Originally published on Code for America’s blog.

When I set out to hire new engineers at Code for America, I hadn’t been there long myself. I remembered how painful a job hunt is and wanted to do hiring differently. Plus, Code for America is committed to building a team that’s as diverse as America, a goal I enthusiastically shared. Most hiring processes are built for the convenience of companies and managers, not applicants. That seemed like a mistake given how hard it is to find developers now, so I tried a number of experiments. Some worked well enough that I wanted to share the results with the public.

Making the job description

The job description is the only thing most potential candidates will see. Given that, it’s a mystery to me why so many of them are terrible. That worked to my advantage, though; being obviously better wasn’t much more work. Some of the things we did:

- Sell the job—At Code for America, we want people who care about our mission. To that end, we opened with information on why this job fit in with our mission, and we talked a bit about their average day so that they could see themselves working here.

- Minimize requirements—Too many job descriptions have a long list of requirements that aren’t really required. This not only discourages good people from applying, but it does so in a way that introduces bias. We only listed the things that we weren’t willing to compromise on. Some were technical skills, but others included, “love making things that serve users” and “enjoy mentoring colleagues.”

- Don’t require a particular language—A good programmer can learn a language quickly, especially when it’s one that colleagues know.

- List nice-to-haves—We had a long list of “optional bonus points”. Our hope with this section was to give a better idea of what we were after, and to make it easier for potential candidates to see themselves in the role because they matched.

-

Get lots of feedback—After my first pass writing this job description, I thought it was pretty solid; I’ve done a lot of hiring before. But because we were working hard to maximize diversity in the applicant pool, I circulated the job description far and wide. Friends, former colleagues, other hiring managers, and diversity-related organizations all gave invaluable feedback. It was humbling to realize how many things could have accidentally discouraged great candidates from applying. The rounds of revision were painful at the time, but I’m glad we did them. Heartfelt thanks to Kane Baccigalupi, Neha Bagchi, Winnie Chen, Juanita Leveroni, Nicole Sanchez, Ellen Spertus, and Diane Tate for feedback.

- Make applying easy—According to programmer Larry Wall, the three great virtues of programmers are laziness, impatience, and hubris. Trying to work with that, I made it so that people could apply by emailing me two links and a few thoughtful sentences. No forms, no hoops, just a quick note.

You can see what we ended up with via the Wayback Machine.

Raising a ruckus

There’s enormous competition for the attention of qualified engineers right now. We did our best to get the word out, including:

- Use a good public url—As a developer, I know I’m much more likely to click on a clear, readable URL than something that looks like line noise. We went with

http://www.codeforamerica.org/jobs/chime/. - Tell your friends to share it—Some of our best candidates came from Facebook posts, tweets, and emails to friends. Don’t forget to ask the folks who provided feedback; having contributed, they’ll be especially eager to make sure their work doesn’t go to waste.

- Tweet the heck out of it—I posted a few obvious tweets about it, ones with enthusiastic copy and great photos of my colleagues. I also pinned one of those at the top of my profile and made sure to mention that I was hiring every few days. Twitter was our best source for candidates.

- Promote the tweets—We tried a number of different ad approaches, but nothing got us as good a response per dollar as promoted tweets. Twitter’s ability to target both geography and the followers of particular accounts let us be very specific in advertising to people and groups that were likely to yield a good response.

- Try other ads—We didn’t have much luck here, but most ads were inexpensive to test out.

- Go to events—We went to the Tech Inclusion Career Fair, which was great. We talked to a lot of people in a short span, reaching both them and, often, their friends. It was also humbling to be one of circa 3 white guys in a large, packed room. It gave me a good emotional appreciation of how much our industry’s lack of diversity can be intimidating to others.

Responding to applicants

In talking with people about their job hunts, their number one frustration was lack of response. That seemed fair to me. They put in time to apply; shouldn’t we put in time to read it? But what most applicants don’t see is the tidal wave of applications that are basically resume spam. Generic resume. Generic cover letter. No indication of interest in the actual position. No indication of putting any time in. How to reconcile those two things? My approach:

- Require a little work—In the job description I required a short answer to 1 of 5 questions. Doing that was less work than writing a proper cover letter, so I didn’t feel too bad about asking. And I tried to make the questions interesting to a wide range of developers. Anybody who didn’t do the work was ignored.

- Respond within 24 hours—If somebody jumped through my hoops, I tried to respond within 24 hours to everybody. If possible, I’d reply in minutes. During this time, hiring was my first priority.

- Make it a personal response—When I replied, I’d make it clear that I read what they sent me, referring to past jobs, GitHub projects, or their question answers as appropriate.

- If they didn’t meet the requirements, ask—About half the people who applied apparently didn’t qualify and didn’t say why they were applying anyhow. As long as they had followed other instructions, I’d ask further. Often people really were unqualified, but some just had relevant skills or experience that just weren’t clear from the resume.

- If they did, book a visit—At this point, anybody who could possibly do the job was invited by for coffee. I made clear that this wasn’t an interview. We were just going to talk about the position and the work. After that, if there was mutual interest we’d book them for our first-round interviews.

First-round interview

Most tech interviews are frankly awful. The two most common activities are solving puzzles and writing code on a whiteboard. I’ve been on both sides of the standard interview and I’ve decided it’s a giant waste of time. Why? It’s nothing like the actual work.

Normal interviews are tuned to make interviewers feel smart and powerful, not to find great colleagues. My solution is to make the interviews more like day-to-day job activities. The first round was about the ability to code and their technical knowledge. I started with a 90-minute pair programming interview. Pair programming, for those who haven’t tried it, is where two developers sit down with one computer and collaborate on solving a problem. It’s my favorite interview technique. Things that made this work well:

- Let them pick the language—For our project, the main language was Python. But it’s not a hard language to learn, and we already had people on the team who knew Python well. By letting the interviewee pick their strongest language, I got to see them at their best.

- Let them use familiar tools—Last time I was hiring I used a standard workstation. But this time I tried letting them use their own computer if they wanted, along with whatever editor they preferred. This worked better. Some people get nervous when struggling with unfamiliar tools, which made it harder to tell their real skill level.

- Use the same problem—I used the same exercise for each person, the Mars Rover kata. This let us more fairly compare candidates.

- Start them off right—I had both the problem and some starter files on a USB key. I’d help them get the sample test up and running. I’d then generally write the next test or two as a way to get them going. I wanted them to have as much time as possible to show me their real coding skills.

- Help them along—We all make dumb mistakes. As a good pair should, I’d help them see the issue when they got stuck. I’d also sometimes jump in to add a test that would expose an issue with their implementation. Not only did this make for a fairer and more realistic test (in the job, they’d also be getting help from colleagues), but it let me see how good they were at collaborating.

After we were done with the pair programming section, we’d turn to a whiteboard. I’d sketch a real-world technical scenario and we’d talk about how it worked in practice. My goal again here was to get an understanding of their strengths. I’d start broad, so that everybody had something sensible to say. Then I’d drill down on particular things, probing for technical depth. One of my goals while doing this is to find something that they know that I don’t. I want them to feel challenged, but never humiliated.

One interesting mistake I made here was in picking the Mars Rover kata. It seemed like a reasonable choice to me and others on the team, but it introduced a bias. Some people, typically those with science-ish backgrounds or long coding experience, took naturally to the problem. But for others, the notion of a Cartesian grid was novel. That caused anxiety and delay as they struggled with what I had wanted to be the easy part. I gave extra time to compensate, but next time I’d just pick a sample problem that is either more related to the project domain or more generally appealing.

Blind review

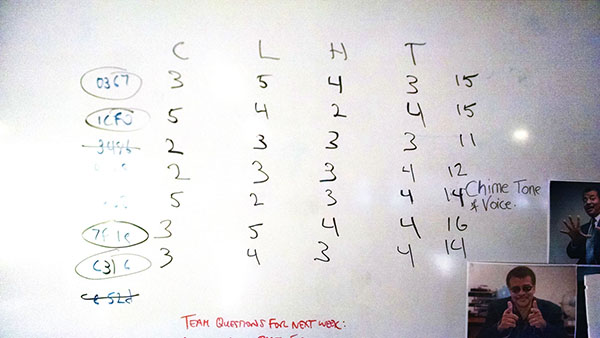

Once we had a reasonable number of interviews completed, the question was who to bring back for the next round. Keenly aware of how easy it is for bias to creep in, we tried blind reviews of the code. To do that, I checked each interviewee’s code into a private GitHub repository, with each directory named for a hash code of the interviewee’s name. (The real name was also checked in, but encoded so that it wasn’t easily visible.) The developers on the team reviewed the code, sat down together, and ranked each applicant on four axes: completion, low-level code quality (that is, how it looked line by line), high-level code quality (taking it as a whole), and test quality. We ended up with a whiteboard like this:

Once we had ranked the code samples, I pulled out my notes from the pairing sessions and we talked a little about impressions, especially how good they were at collaborating, and how they did on the technical discussion. That led us to pick four people to bring back for second-round interviews.

Second round

Running again with the theory that interviews should be pleasant and similar to a normal day at work, we booked candidates for a 2-hour session with the team. The first hour was a relatively relaxed joint discussion. We all talked about our backgrounds, discussed the work and the industry, and got to know each other a bit. We tried to keep the tone casual and the mood friendly. Too many interviews feel like inquisitions, and that would give the wrong impression about Code for America, a collegial place. In the second hour, the non-developers left; the rest of us had a focused discussion about a feature we planned to add. Here the goal was to see how the candidate thought, both from a technical and a product perspective. Could they see which features were key and which should be left for later? Were their implementation choices practical? Could they adjust their architectural notions if the use case changed? Were they good at collaborating, being neither too controlling nor too obedient?

Making offers

Ranking, surprisingly, was pretty easy. After each second-round interview, we spent 10 minutes or so discussing the candidate, and then sorted them by rank. There was no serious disagreement, and by the time we had completed all four second-round interviews, we were ready to make offers. I had intended to send offer letters out immediately, but didn’t realize that there was a few days’ lead time. Next time I’d start work with HR to prepare blank offer letters when we started the second-round interviews so that we could respond more quickly.

The other change I’d try to make was to find ways to have hiring be less batch-oriented. In my previous startup experience, recruiting was an ongoing effort; when we found somebody good, we’d hire them. But here we were trying to fill a single position, so it made sense to see a bunch of people and pick the best. It made sense from the hiring side, anyhow, but for most candidates it resulted in a fair bit of lag time between initial contact and decision. They were understanding and I tried to keep them updated, but it still would have been much better for everybody if we could have given them faster answers.

Conclusion: go do it!

My main conclusion from this was that making hiring easier and fairer wasn’t that hard, and it was certainly worth the effort given the quality of the candidates we got. You may not have the time to try everything I did here right away, but don’t let that stop you from tweaking one thing and seeing how it works. Good luck, and feel free to contact me with questions or feedback via Twitter.